Fossil fuel divestment: An FAQ for the Cornell community

As Cornell’s shared governance groups consider resolutions related to the divestment of fossil fuel-related holdings from the university’s endowment, these FAQs provide some background for the campus community.

What has Cornell done in the area of sustainability?

Sustainability has been an important value at Cornell for decades. Cornell’s first energy conservation initiative was begun in 1985. Lake Source Cooling, our renewable source of chilled water on campus, was implemented in 2000. The following year, Cornell became the first university to sign the Kyoto Protocol. In 2005, Alice Cook Hall became the first LEED certified building on campus.

Since then, Cornell has redoubled its efforts toward sustainability in campus operations, as we work toward our goal of becoming a carbon-neutral campus, using 100% renewable energy, by 2035. Cornell’s commitment to this goal was one of the most aggressive and earliest of major universities, and serves as an important reflection of our values.

Over the past decade, Cornell has reduced its carbon emissions by 37%, constructing efficient buildings and retrofitting older ones, and implementing programs such as our Energy Conservation Initiative, which replaced lighting in indoor and outdoor spaces with energy-efficient LED bulbs, saving the campus more than 18,000 tons of carbon emissions.

Solar power is another way Cornell is trimming its carbon footprint. In 2019, the university’s sixth large-scale solar project went online, doubling the university’s offsets from renewables and adding enough electricity onto the grid to serve about 3,000 average residential homes. We also joined more than 20 universities to launch the New York State Higher Education Large Scale Renewable Energy Consortium, a group that is working to achieve 100% renewable electricity use through combined purchasing.

Looking forward, Cornell is investing in the exploration of new technologies like Earth Source Heat, which has the potential not only to enable us to achieve our goal of carbon neutrality, but also to be exported for use elsewhere, decreasing carbon emissions beyond our own campus. Cornell is viewed as a leader in sustainability, achieving a “gold” rating by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education’s (AASHE) Sustainability, Tracking, Assessment, and Rating System (STARS) for eight years running.

Cornell also boasts some of the world’s leading researchers and experts in all facets of sustainability – from climate change to sustainable agriculture, renewable energy and conservation, to name just a few. Our Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability has more than 550 faculty fellows, who both conduct research and teach courses on sustainability. Many of these faculty members are also directly engaged with policymakers at the local, state, national and global levels helping to address the global climate crisis.

Learn more about Cornell’s work to be operationally sustainable on our Sustainable Campus website, and about our educational and research work on sustainability on the Cornell Atkinson website.

What is an endowment?

An endowment is a fund that consists of financial resources that have been donated to a nonprofit organization, like a university, for specific purposes. Cornell, like most universities, manages its endowment with the goal of ensuring that when a donor provides funds for a specific purpose, there will be sufficient resources to support that purpose in perpetuity.

For example, if a donor contributes money to pay for the salary of a professor, creating a “named” professorship, the money must then be managed to cover the professor’s salary forever. To achieve this goal, the gift must be large enough that the payout in the first year covers the cost of the salary, with the principal remaining invested. (The payout is the amount of endowment dollars that the Board of Trustees approves for spending each year.) In the years and decades that follow, the original gift must grow enough so that the annual payout covers the salary and the amount that the salary will have grown due to inflation.

Endowments are thus invested for growth. They are invested in stocks, bonds and a range of other financial instruments. Cornell’s Board of Trustees, a group of 64 people – including students, employees, faculty and alumni who are elected by their respective groups – has ultimate responsibility for the endowment. Board members are all volunteers who are not paid by Cornell, with the exception of the president and the employee- and faculty-elected representatives. The Board of Trustees delegates direct oversight of the endowment to its Investment Committee, which establishes policies for managing the endowment; the Cornell University Office of Investments is responsible for implementing those policies.

The Office of Investments is best seen as a “manager of managers;” it hires and authorizes external investment managers to purchase, sell and transfer the assets of the endowment. This approach is common among universities of Cornell’s size.

The payout from the endowment is a very important source of support for the university, providing about 10% of the operating revenues for the Ithaca campus, and 7% of Cornell’s total operating revenues. More than a quarter of the endowment’s payout supports student financial aid.

Does the endowment reflect Cornell’s commitment to sustainability?

The principal purpose of the Cornell endowment is to provide income for the advancement of the educational and mission-related objectives to which the university is dedicated, and the first responsibility of the Board of Trustees is to ensure that the funds are managed properly and used for the educational and programmatic purposes for which they were donated.

Over the past decade, it has become feasible to make investments consistent with these objectives while also seeking a level of commitment to good environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices. In fact, many of the external investment managers that are retained by Cornell have committed to investment decisions governed by formal ESG polices, such as the United Nations Principles of Responsible Investment (UNPRI).

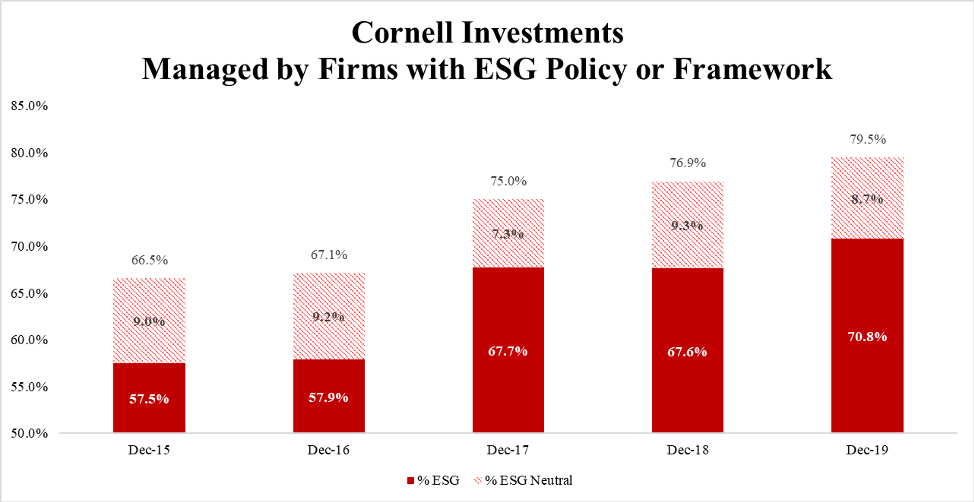

The proportion of the endowment under management by organizations with formal ESG policies and frameworks has increased from 57.5% in December of 2015 to 70.8% in December of 2019. Another 8.7% is currently managed in accounts where UNPRI or other ESG policies/frameworks are not directly relevant, including accounts with primarily cash and U.S. Treasury holdings. In combination, these two categories represent about 80% of current endowment holdings.

As of December 2019, Cornell’s stock and bond holdings in firms included in the Carbon 100 Oil and Gas list and Carbon 100 Coal list represent about 1.0% and 0.3% respectively of the total value of the endowment. As noted above, Cornell does not purchase these holdings directly, but uses outside managers that oversee its investments.

What is divestment?

In the context of an endowment, divestment means selling all investments in a particular sector. The current conversation surrounding divestment is focused on the university’s investments in companies that profit from the sale of fossil fuels, including oil, gas and coal. It is important to note that divestment cannot happen overnight: many of the investments in an endowment are “locked up,” with requirements that they be maintained over a period of years. Thus, if there were to be a decision to divest from some sector, it would have to be rolled in over time.

The white paper (pdf) that accompanies the resolutions being considered in our five shared governance assemblies (the Student Assembly, the Graduate and Professional Student Assembly, the Faculty Senate, the Employee Assembly, and the University Assembly) does an excellent job of laying out arguments for divestment, and is worth reading.

Arguments against divestment come in several forms. One set of arguments focuses on negative economic impact: Divesting from one sector could have significant economic costs for the university, both direct (i.e., if the sector is profitable), and indirect (e.g., stemming from the trading costs associated with selling the assets and the costs of ensuring compliance, i.e., checking that no assets associated with the sector are in the endowment).

The second group of arguments focuses on the loss of influence that arises when you divest from a company. When you own shares in a company, you have the right of “proxy voting,” which helps to guide the policies and practices of that company. If Cornell were to divest from companies that currently produce fossil fuels, it would lose its proxy voting rights in those companies, and thus the ability to push those companies away from fossil fuels and into the alternative energy areas.

What process does Cornell have for divestment?

The Board of Trustees has in place a set of policies that specify when they will consider divestment, as well as standards that must be met for a divestment decision. Specifically, the board will consider a proposal for divestment from the Cornell community when either the President forwards a resolution from one of the shared governance assemblies, or all five of the assemblies support such a resolution. Once the board takes up consideration of divestment, they will divest only when:

- a company’s actions or inactions are “morally reprehensible;” and also

- the divestiture will likely have a meaningful impact toward correcting the specified harm and will not result in disproportionate offsetting societal consequences; or

- the company contributes to harm so grave that it would be inconsistent with the goals and principles of the university.

These policies were adopted by the Board in early 2016. At that time, the board was responding to resolutions from all five shared governance groups calling for divestment from fossil fuels. Since then, the investment landscape has changed considerably, as noted above in the discussion of ESG principles. Sustainability broadly, including the issue of consideration of fossil fuel divestment, was discussed informally at the January board meeting, and it is anticipated that the issue will be considered again if the resolutions currently under consideration are advanced to the board.